Can you control everything that is carried through an airport or onto a plane? Most of us are familiar with metal detectors, and the long queues that accompany checking-in. But new technologies are hoping to not only decrease the time you wait before jetting off on holiday, but also more tightly control what, and who, is taken onboard.

However, whilst this sounds like a marvellous plan, appealing to every world-weary explorer, business traveller or family with screaming kids, there is a certain amount of debate associated with the technologies at the core of the strategy.

The approach is founded on the evolving concept of biometrics, the study of methods for identifying people based upon their physical or behavioural traits. The concern is that, to be identified by these means, there must somewhere be a database of our personal traits. The technology could potentially allow us to be identified out of a crowd without our consent. Is this storage of information a breach of our civil liberties? Should we always be being watched? Or is this technology simply too crucial for law enforcement not to pursue?

Old and New Technology:

The word biometrics comes from the Greek words bio and metric, meaning “life measurement”. It is the study of methods for identifying people based on their behavioural or physical characteristics and includes well-known methods such as fingerprint analysis, which is used on every visitor entering the US, as well as retinal and iris scans, facial and voice recognition techniques, and behavioural recognition procedures that can identify you by your walk.

Airports have always been very concerned about their security. Let's have a look at some of the technologies currently being used, and investigate the progression from old-fashioned x-ray machines, to modern biometric tools.

Metal Detectors and X-Rays:

On checking in, every traveller in every airport around the world walks through a metal detector. Metal detectors work by electromagnetic induction – changing magnetic fields cause changing electric fields in metals, and vice versa. When a piece of metal is near the changing magnetic field being produced by the detector, electrical currents are induced in the metal, which then produces an alternating magnetic field of its own. This new magnetic field can then be detected and is why you need to remove metal objects like your belt when you walk through airport security.

On checking in, every traveller in every airport around the world walks through a metal detector. Metal detectors work by electromagnetic induction – changing magnetic fields cause changing electric fields in metals, and vice versa. When a piece of metal is near the changing magnetic field being produced by the detector, electrical currents are induced in the metal, which then produces an alternating magnetic field of its own. This new magnetic field can then be detected and is why you need to remove metal objects like your belt when you walk through airport security.Whilst you are walking through the metal detector, your bags are passing through an X-ray machine. As they move along the conveyor belt, X-rays, which are electromagnetic waves like light but much more energetic, are shone on the luggage. Many of the X-rays pass through unblocked by your suitcase and its contents, and detectors on the other side of your luggage measure how many of these X-rays make it through. By knowing that different things absorb different energy X-rays, a picture of your bag’s contents can be built up.

Explosives and Drug Detection:

Dogs have been used to sniff for explosives and drugs for many years, but it was only in 2003 that Explosive trace detection was introduced at Sydney airport. This system employs Ion Mobility Spectrometry. Firstly, a sample is taken by wiping a swab on your luggage or clothes. The swab is placed in the detector, and the sample is ionised – converted from its molecular form into its ionic (charged) form. The ions are separated by an electric field – different mass ions move at different speeds towards the detector, and so the time taken to arrive at the detector tells us if the telltale explosive, or drug, signature is present.

Another new method of explosive detection is terahertz spectroscopy. This technique uses radiation with a frequency between microwave and infrared, and can be more useful that X-rays as, although both X-rays and terahertz radiation can see through material, terahertz rays are non-ionising and so harmless to humans. They can also probe for chemical information, rather than just physical shape information, as many molecular excitations are within the terahertz frequency band.

Andrew Burnett, terahertz spectroscopy expert at the University of Leeds, says that the information obtained from terahertz spectroscopy is more sensitive than other radiation:

“This information is very specific, even allowing us to differentiate between different forms of the same drug… The aim is to eventually produce a system that gives us chemical specific information through clothing.”

Fingerprint analysis:

Fingerprint analysis is the oldest form of biometric identification, and is still regarded as one of the most reliable. Every visitor to the US has his or her fingerprint read on entry through an airport.

A fingerprint is an impression of the raised areas of epidermis – called friction ridges – on your finger, and everyone’s fingerprints are unique. You leave your fingerprints behind on things you touch by depositing the natural secretions – mainly water – from the eccrine glands in the friction ridge skin. These are called latent, which means hidden, fingerprints. If contaminants on the skin are also left behind, such as dirt, then they are called patent fingerprints. Patent fingerprints are easily seen by the human eye and so can be photographed and then identified as they are. Latent fingerprints are made visible by electronic, chemical and physical processing techniques such as “dusting” a crime scene.

Fingerprint analysis was traditionally completed manually by comparing the fingerprint with ink fingerprints on paper. As you can imagine, this was a very time consuming task. Modern day techniques are able to match fingerprints by using computerised databases.

An interesting fact is that the koala is one the few mammals that also has fingerprints.

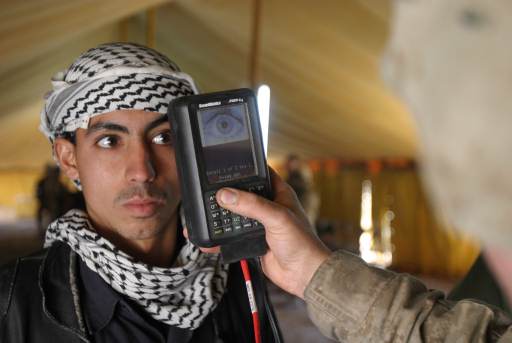

Iris and Retina Recognition:

Iris scans look for patterns based on high-resolution camera images of the iris, whose intricate structure is unique to the person. Identification is unambiguous and as long as you do not damage your eye during your life, your iris scan will not change. The technology has been employed at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands since 2001 to allow passport-free travel. The United Arab Emirates has such systems at all 17 air, land and seas ports.

Iris scans look for patterns based on high-resolution camera images of the iris, whose intricate structure is unique to the person. Identification is unambiguous and as long as you do not damage your eye during your life, your iris scan will not change. The technology has been employed at Schiphol Airport in the Netherlands since 2001 to allow passport-free travel. The United Arab Emirates has such systems at all 17 air, land and seas ports.Retinal recognition is slightly different, as the scan maps the capillaries feeding blood to the retina. These blood vessels absorb light more readily than the surrounding tissue, and when a ray of low-energy infrared light is shone into the eye, the reflection of the light, which depends on the capillaries, is measured. Even identical twins have different retinal scans, and like iris recognition, your retinal scan will stay the same throughout your life.

Facial Recognition:

Facial Recognition is a relatively new technology that compares facial features in the live image with those in a database. The Australian Customs Service’s SmartGate system compares the face of the examined with their image on their ePassport microchip, and replaced manual passport checks for Qantas staff in 2003.

Facial recognition is the way forward for the aviation industry, with the International Civil Aviation Organisation issuing a resolution endorsing the use of face recognition as the:

“globally interoperable biometric for machine assisted identity confirmation with machine-readable travel documents.”

Voice Recognition:

These days, it seems every time you call up your phone company or book a cab, you talk to a machine. These systems are based around voice recognition technology.

Clive Summerfield, biometrics and voice recognition expert, and CEO of Three S Holdings Pty Ltd in Canberra, thinks that over the next five years, voice biometrics will eclipse iris and facial scans and become second only in market share to fingerprinting systems.

“Voice recognition, when configured correctly, is 10 times more accurate that face, 2-3 time more accurate than fingerprint and approaching the performance of iris.”

Passports:

A new Australian passport, the biometric ePassport, was introduced in 2005 and has an embedded microchip that stores the holder’s photograph, name, gender, date of birth, nationality, passport number, and expiry date. European countries are currently issuing passports that have the owner’s photograph and fingerprints on the chip. The US passport has a chip that is big enough to store additional biometric information such as facial recognition and retinal scan information.

A new Australian passport, the biometric ePassport, was introduced in 2005 and has an embedded microchip that stores the holder’s photograph, name, gender, date of birth, nationality, passport number, and expiry date. European countries are currently issuing passports that have the owner’s photograph and fingerprints on the chip. The US passport has a chip that is big enough to store additional biometric information such as facial recognition and retinal scan information.Will biometrics really shorten airport queues?

Even if these new technologies work perfectly inside the airport, they will not shorten check-in queues if the public does not like them or cannot use them. M. Angela Sasse, Professor of Human-Centred Technology at University College London, researches the usability of security systems and concludes that even if a system works well, it will not gain approval if it is not easy to use or looks unpleasant. A recent iris scan trial at Heathrow airport, in which participants could not adjust the height of the scanners, and a recent US airport trial, in which dirty fingerprint readers were used, are examples of poorly designed systems.

“You should design all the processes the traveller encounters to be as easy and pleasant as possible … Make sure the system is clean and pleasant to use.”

The ethics and future of biometrics:

Identity theft is one of the fastest growing crimes in the world, and estimates have valued identity-related crime as a $2 trillion problem. Biometrics is seen as a potent weapon in the fight against identity theft, however the concern surrounding biometrics is that there must somewhere be a database of your traits. Could someone steal this information? The common fear is that once your fingerprint or retinal information is stolen, it is compromised for life, as these patterns never change.

What differentiates biometrics from other forms of security is that there must be a match between the “live” biometric scan, and the “stored” information. Unless an identity-stealer has recreated your facial expressions or other biometric information to the minutest detail, they will not be able to pass through security.

Mathew James, Managing Director of UK Biometrics Ltd., says that the fingerprinting technology used by UK Biometrics is ethically sound as a biometric thief is likely to just end up with a bunch of useless numbers:

“We do not store fingerprints and it is impossible to recreate a fingerprint from the data we store. Our scanners register up to 17 minutiae points on a fingerprint, convert these into data which is then encrypted for future comparison. Even if this data were stolen, the thief would have a lot of meaningless numbers, useless without the scanner and its attendant technology.”

Whilst biometric technologies may tightly safeguard information, desperate thieves can, however, always find a way. In 2005, Malaysian car thieves cut off the finger of a Mercedes-Benz S-Class owner when attempting to steal his car so that they could use his fingerprints to start the vehicle. And the popular television show MythBusters broke into a secured building with a photocopied fingerprint.

Stephanie Schuckers, Associate Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering from Clarkson University, conducts research into how to prevent fingerprinting systems from being spoofed by creating fake fingerprints out of such materials as Play-Doh, and thinks that biometric security systems are an improvement on traditional methods, even if there may be some vulnerabilities.

“I try to caution people to ask, what is your security question and what is your solution now, and does biometrics improve this in terms of whatever your goals may be – convenience, improved security. Just because there is a vulnerability – well all security systems have a vulnerability – it doesn’t mean it’s not necessarily a technology that might (not) be useful.”

Schuckers raises the example of a passport, and says that by adding a biometric element, you take a step forward to improved security.

Schuckers raises the example of a passport, and says that by adding a biometric element, you take a step forward to improved security.“The current state of passports is a photo that may be 10 years old and a guy looking at you to see if it matches. Would adding a fingerprint improve the security at the borders? I would argue that that would be a step above the present technology. Can someone somehow slip a thin fake finger over their hand? Sure. That’s the state of the technology now, but you’ve made steps to improved technology.”

She believes that whilst there may be some vulnerability in biometric systems, they can be overcome by a combination of systems that would make it extremely difficult for the identity stealer to be successful.

“You can make it more difficult for someone to spoof the system by combining say a fingerprint, a card, and a PIN. So now your potential identity stealer would have to have all of those items to access the bank account… There are very simple steps that you can take now with commercially available devises that would minimise the risks”

Whether or not identity theft is likely or even possible, biometric systems are more and more being within society, with facial recognition software used in Closed Circuit Television (CCTV) all over the UK. Is this a breach of our privacy? Should Big Brother track our every move?

Schuckers believes that these are serious questions that need to be addressed by society, but that they also open up research areas to maintain the security of your personal information.

“I think those are reasonable questions that we need to ask as a society. What applications are meaningful that you would take the trade-off between privacy and the extra security you might get using the biometrics? I also see it as a research avenue. There are a lot of people researching ways to use biometric information in such a way that doesn’t actually give up your private information.”

Clive Summerfield sees the issue as a legal one, revolving around privacy and storage of sensitive personal information, as opposed to the technical challenge of safeguarding the information.

“At the end of the day, I think this will become a legal issue, where the privacy, protection and confidentiality of such information becomes legislated and that senior executives of organisations collecting, using, communicating and storing biometric information will become legally responsible for any breaches, along with biometric systems developers, implementers and vendors, who will be required to certify that their system implements the functions necessary to protect the biometric information.”

He draws a parallel with the postal service, in which stealing a letter is a federal crime, and thus protects the confidentiality of the contents of letters. There is a similar law regarding eavesdropping on telephone conversations, and these systems are widely accepted by society, despite the fact that there is little or no technological protection of information conveyed in these ways.

“Similar legal protection needs to be in place for biometrics for the mainstream of society to start to access biometrics… Anyway, I’m no legal expert – so how you go about implementing such laws, I’ll need to leave to the legal experts!”

Another concern is the storage of personal information on a single chip in your passport. Data on the chip can theoretically be stolen using wireless technology, and even if the information is encrypted, experiments in the Netherlands showed that the Dutch passport encryption could be cracked within two hours. Whilst you would never be able to set up the sensitive equipment to steal the information in our ever-more secure airports, the same could not be said about hotels and other places where you need your passport.

Mathew James thinks that in any situation in which there is a need to make sure of a person’s identity, there is a future for biometrics:

“Think of the number of keys, swipe cards, prox fobs and PINs that keep a modern airport secure. They can all be replaced by the one key which cannot be lost, stolen, forged or hacked – the human fingerprint. People can be added to, or deleted from, the system in seconds. Security staff can ‘access all areas’ without carrying a bunch of keys and passengers need only ever register once.”

As for biometric passports?

“We see a future where the only passport you will ever need will be your fingerprint, registered once in your home country.”

this given that there are the same 100 horrible channels with no content everywhere in the country, but people do love their tv's so maybe they are on to something.

ReplyDeleteMelbourne CCTV

The content looks real with valid information. Good Work

ReplyDeleteDavid Laid

The content looks real with valid information. Good Work

ReplyDeletethis website

#1 The Best Apps and Games For Android · Apk Module

ReplyDeletehttps://apkmodule.com/geometry-dash-apk/

Geometry Dash APK

Great, thank you for your article. Come to Getmodnow - where you can download Terraria game version 1.4.4.9 APK completely free! We pride ourselves on being a trusted resource for passionate players, providing the latest and greatest version of the Terraria game at no cost. At Getmodnow, we give you the opportunity to experience Terraria with the full features and diversity of version 1.4.4.9 APK. You will explore the magical world of Terraria, where you can build, fight and explore in an unlimited environment.

ReplyDelete"Baba Nyonya cuisine is truly a hidden gem! The unique blend of Chinese and Malay flavors makes every dish special. I recently tried their signature dishes, and they were amazing. By the way, if you enjoy exploring cultural experiences, you might also like some fun traditional games online. Check out TeenPatti Boss for an exciting card game experience.

ReplyDeleteInteresting article on biometrics and border security! Just like modern technology strengthens safety and efficiency, Daly's Construction applies advanced ICF building methods to ensure strong, energy-efficient, and future-ready construction projects in Ireland.

ReplyDeleteBiometric technology is indeed transforming border security by making identification more accurate and reducing the chances of illegal crossings. While reading about these advancements, I was reminded of how digital platforms also rely on security and trust to grow their user base. For example, entertainment apps like Star Game APK

ReplyDeleteensure user safety through secure transactions and verified systems, showing how technology plays a vital role across different industries in building confidence.