Two minisubmarines planted a titanium alloy Russian flag on the ocean surface, 4261 m under the Arctic Ocean surface at the North Pole. It is the first time the technical feat of reaching the North Pole sea floor in a manned craft has been achieved and is not only a sign of Russian strength, but a clear indication of the fact that Russia wants to claim the possibly resource rich area. The submersibles were named Mir-1 and Mir-2 – clearly Russia has a penchant for calling their scientific explorer craft Mir.

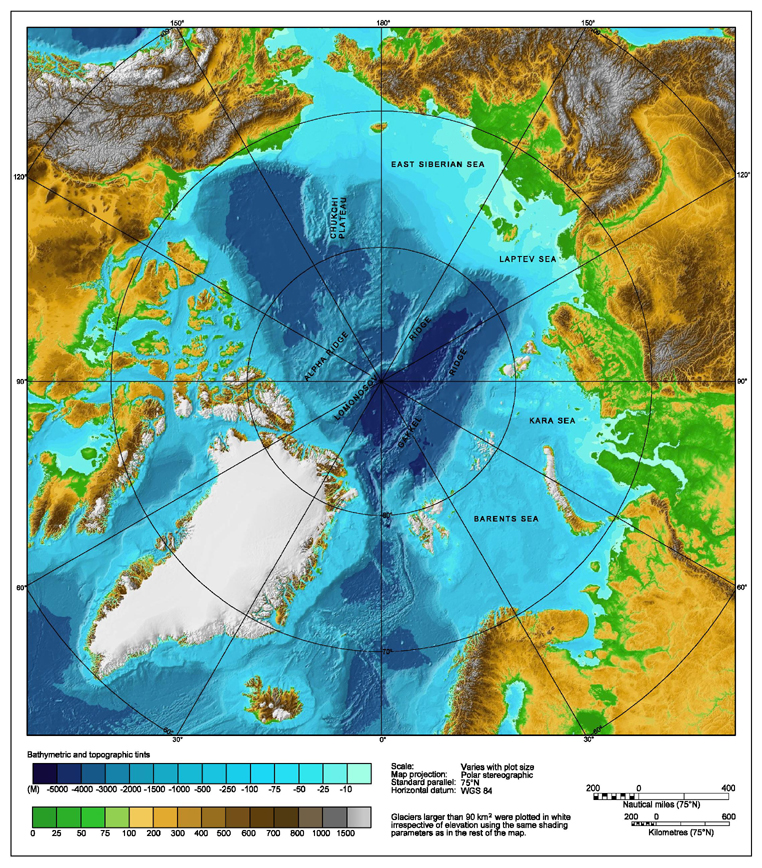

Although politically charged, the trip had a number of scientific aims. Soil and water samples of the seabed were taken during the mission. The mission could also help sort out whether or not the Lomonosov Ridge, which runs between Russia and Greenland and on which the disputed region lies, is actually part of, or connected to, the Russian continental shelf.

Under international law, out to 12 nautical miles, a coastal state is free to set laws, regulate any use, and use any resource. Out to 200 nautical miles, a coastal state has an Exclusive Economy Zone and has sole exploitation rights over all natural resources. If there exists a continent shelf beyond this, then the coastal state can claim exploitation rights out to that point.

This is where the debate lies – the North Pole sits nicely between, and off the continental shelves of, Greenland (Denmark), Russia, Alaska (USA), Canada and Norway. Russia wants to establish that the Lomonosov Ridge is an extension of its continental shelf. Indeed, the wording of the United Nationals Law of the Sea is not too clear and allows a country to claim jurisdiction if the geology of the seabed is similar to the nearby continental shelf.

Russia had a claim denied by the UN in 2001, as it appears the ridge is separated from Siberia by a trough. Denmark had their claim rejected for similar reasons. However, the Russian claim looks slightly stronger as the geology on each side of the trough is similar, and it appears that the trough was created by the seafloor moving apart – perhaps the Lomonosov Ridge was once part of Siberia. The 2001 decision did not so much reject the proposition, more that more research needs to be done. Norway also submitted a claim in 2006.

So why bother with the treacherous journey? This was a trip in which the submersibles could easily have missed on return the opening in the ice created by the team’s nuclear powered icebreaker.

The reason, as it so often is these days, is oil and energy. According to the US Geological Survey, around a quarter of the world’s oil reserves are locked up below the icecaps of the Arctic Ocean. In a world where oil could run out sometime in the not too distant future, and alternative energies are not yet solving the world’s energy demands, access to traditional energy sources is vital.

The Arctic floor is also home to massive unexploited gas fields. The Russian Shtokman field has an estimated reserve of 3,200 billion cubic meters of natural gas. Global warming is shrinking the ice that previously covered the surface, and the shrinking pool of global energy resources makes the extremely costly mission of salvaging these resources more profitable. The less ice there is, the easier it is to get at.

The Arctic floor is also home to massive unexploited gas fields. The Russian Shtokman field has an estimated reserve of 3,200 billion cubic meters of natural gas. Global warming is shrinking the ice that previously covered the surface, and the shrinking pool of global energy resources makes the extremely costly mission of salvaging these resources more profitable. The less ice there is, the easier it is to get at.

Added to the increased energy portfolio is the prospect of controlling a new Northwest Passage across the Arctic year-round.

Norway, Denmark and Canada are also attempting to establish their own sovereignty over the region, whilst the British Navy has increased Arctic patrols. Canadian and Danish scientists are currently mapping the north polar sea on two icebreakers, and Canada recently announced it would spend $7.4 billion Canadian to build up to eight armed ice-breaking naval ships to patrol its Arctic claim.

The Russian voyage is part of the ostensibly science research based Arktika 2007. The crew of MIR-1 comprised the pilot Anatoly Sagalevich, Soviet and Russian polar explorer Arthur Chilingarov, and Vladimir Gruzdev. The crew of MIR-2 comprised pilot Yevgeny Chernyaev of Russia, Mike McDowell of Australia and Frederik Paulsen of Sweden.

The MIR submersibles can dive to a maximum depth of 6000 meters. This makes them two of only five manned submersibles in the world that can dive deeper than 3000 m.

“Our mission is to remind the whole world that Russia is a great polar and research power,” said expedition leader Artur Chilingarov.

Anti-climatically, Gruzdev said:

“There is yellowish gravel down here. No creatures of the deep are visible.”

The mp3 for this podcast is here

It’s great to be here with everyone, I have a lot of knowledge from what you share, to say thanks, Maps International voucher codes

ReplyDeleteIt is truly a well-researched content and excellent wording. I got so engaged in this material that I couldn’t wait reading. I am impressed with your work and skill.

ReplyDeleteYou are my breathing in, I possess few blogs and often run out from to post . 바카라사이트

ReplyDelete